The Origins of the Golden Retriever Revisited

By Jeffrey Pepper

Golden Retrievers have become on of the most popular breeds in the United States during the last decade yet there are many who are still confused as to the true origins of the breed. This is not at all surprising as there have been at least two major theories regarding the history of the breed that have been circulated for many years. This article will examine how these theories came into existence and offer some further thoughts on the subject.

Golden Retrievers have become on of the most popular breeds in the United States during the last decade yet there are many who are still confused as to the true origins of the breed. This is not at all surprising as there have been at least two major theories regarding the history of the breed that have been circulated for many years. This article will examine how these theories came into existence and offer some further thoughts on the subject.

For many years it was generally accepted by authorities that our Goldens were the direct descendants of some Russian circus dogs purchased by a member of the English gentry, Sir Dudley Marjoribanks, later the first Lord Tweedmouth. These dogs, we are told, were taken to Tweedmouth’s Scottish estate called Guisachan where they were used to hunt deer. Pleased with their skills, the dogs were bred and later an out-cross to a sandy-colored Bloodhound was introduced to reduce size and improve scenting ability. It was said that all Golden Retrievers were direct descendants of this out-cross breeding.

This colorful story was accepted as the origin of the Golden Retriever breed until the early 1950’s when Lord Tweedmouth’s original studbooks were made available by a descendant of his. Research into these handwritten books by Elma Stonex lead to the publication of new information, which directly challenged the circus dog story.

The studbooks indicated that Lord Tweedmouth had purchased an unregistered Yellow Retriever named “Nous” from a cobbler in Brighton in the year 1865. After hunting this dog for a time, Lord Tweedmouth bred him to a Tweed Water Spaniel (a now extinct breed from Scotland) that had been purchased. This breeding produced a litter of four bitches from whom all Golden Retrievers today are descended. While there were several out-cross breedings done with descendants of this breeding, all Goldens today are direct descendants of Nous and Belle. This is the currently accepted theory of the development of Golden Retrievers.

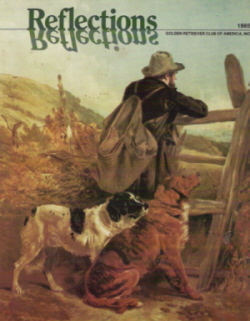

Recent pictorial evidence, combined with some research in books written about dogs during the 1800’s leads me to question the simplicity of the current theory. The chromo-lithograph pictures on the cover of this magazine depicts two dogs, one of which I and many others believe may well be a Golden Retriever. The lithograph is labeled on its back and the information contained there forces me to believe that the Golden Retriever or some breed of dog remarkably similar to the Golden existed for some time prior to Lord Tweedmouth’s purchase of Nous and well before Nous was first bred to Belle.

The chromo-lithograph, which came into my possession about two years ago, is titled “The Game-Keeper” and was done by Edmund Walker after a painting by Richard Ansdell. It was printed by Day& Son in London, England on August 1, 1854, eleven years before Lord Tweedmouth first purchased Nous. I have been unable to find any historical information about Walker who was probably one of many lithographers who produced prints in the style of Ansdell during the mid-Nineteenth Century. Richard Ansdell was born in Liverpool in 1815 and died in 1885. He was a self-taught painter known for his pictures of animals. His works show the influence of the better-known animal painter Sir Edmund Landseer, who lived during the same time. Ansdell became quite popular during his lifetime thanks to engraved reproductions (lithographs) of many of his works. The chromo-lithograph I purchased is one of these reproductions.

Needless to say, I was fascinated by the likeness of the gold-colored dog to a Golden Retriever. In and effort to learn more about the dog and the lithograph, I contacted several people including Pagey Elliott, our GRCA historian; the Dog Museum of America; and the American Kennel Club library. Mrs. Elliott knew nothing about the lithograph at the time, but shortly thereafter learned of a lithograph purchased by Jennifer Kessner, also after an Ansdell painting but by a different lithographer, which pictured another dog extremely similar to the “Golden” in my lithograph. This was a second piece of evidence that Goldens have been around longer than previously thought.

An “Ilchester” Retriever. Color print, signed by Maud Earl, 1906. Courtesy of R. Page Elliott

My curiosity now peaked and I spoke to Mrs. Elliott again. She kindly invited me to visit her home and go through her extensive collection of Nineteenth Century dog books. Much of the information in this article comes directly from these books. In addition, Mrs. Elliott has a collection of numerous engravings and aintings depicting Goldens, including one titled “Retriever on Bank”, said to be by Garrand and painted in the early 1800’s. Most fascinating was a previously unknown print of a Landseer painting, dated October 28, 1839, which depicts two dogs that look very much like Goldens, especially in head structure. This print was discovered by Mrs.Elliott and Kathy Liebler when they searched out Guisachan a few years ago. They discovered the print in a milk house on the abandoned estate and it was later given to Mrs. Elliott by the currant owner of the land. The print is featured at the beginning of the GRCA film on the Golden Retriever.

Edwin Landseer was a friend of the Marjoribanks and were friends of the Royal amily. The locale of the painting referred to is probably Windsor Castle, featuring Victoria and Albert. The original painting hangs in Balmoral Castle. This engraving belonged to the Marjoribanks and at one time hung in Guisachan House. It is possible that the family already owned Golden-like dogs as early as 1839, long before the entry of the purchase of Nous in Lord Tweedmouth’s studbooks.

The first step in my research was to try to discover just what kind of dog the golden-colored animal was. I sent a photograph of the lithograph to the Dog Museum of America. They were unable to identify the dog but forwarded my request for information to the American Kennel Club librarian, Roberta Vesley. She, too, was unable to definitely identify the dog, but suggested that it might be a Setter, since they were a heavier breed of dog at the time, or perhaps a Newfoundland (probably the St, John’s type) as some of the early ones were golden or red in color. Another possible choice she mentioned was one of the Spaniels, even though the dog pictured is quite a bit larger then most Spaniels. About the only thing clear from all of this is that we’ll never know for certain exactly what breed these dogs were, but the two pictured in the “after-Ansdell” chromo-lithograph look amazingly like Golden Retrievers.

But let us go back to the beginning. As interest in the Golden Retriever developed in the early years of this century, there was a natural curiosity about how the breed was developed. The first answer, as we have learned, was the Russian circus dog story. Where did this story start? Probably with Col. The Honorable W.le Poer Trench, an early admirer of the breed who owner the then well-know St. Hubert’s Goldens. Col. Trench became involved with the breed during the latter part of the Nineteenth Century and claimed that his Goldens were bred from dogs he obtained directly from Guisachan in about 1883. Col. Trench claimed that his Goldens were descended from Russian circus dogs (the original theory) and stated that his information came directly from Lord Tweedmouth’s kennel man. As a leading fancier of the breed, Col. Trench’s story was believed and it became the accepted origin of the breed. Because of their foreign heritage, Col., Trench insisted that the breed should be called “Russian Retrievers”. His theory of Russian heritage died hard. It is still mentioned as the origin of the breed in H. Edwin Shaul’s The Golden Retriever, published in 1954.

Another formidable advocate of the “Russian” theory was Mrs. M.W. Charlesworth, another prominent Golden breeder of the early 1900’s and the author of The Book of the Golden Retriever. The circus dog theory was given official sanction by both the Golden Retriever Club in England and the Golden Retriever Club of America until the 1950’s.

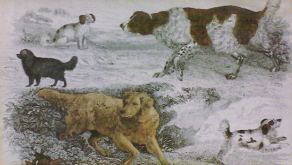

Setters and Spaniels by Reinagle from Daniel’s Royal Sports 1802.

Original copperplate engraving by J. Scott.

Upper right-The Old English Setter: Lower left-The Setter

(Featherstone Castle breeding-not Irish). Courtesy R. Page Elliott

The theory was not universally accepted, however. As early as 1929 the idea that Goldens were descended from Russian dogs was formally challenged by Jacqueline Cottingham in an article published in February 1, 1928 edition of The American Kennel Club Gazette. An article appeared in The Field, an English dog magazine on June 17, 1939. Written by A. Coxton, it challenged the Russian theory and instead stated that a later Lord Tweedmouth, a grandson of the first, had said that the Golden Retriever breed started with a dog purchased by the first Lord Tweedmouth from a cobbler in Brighton. This dog was the only yellow in a litter of black Wavy-Coated Retrievers. Of course, this is the currently accepted theory. Other Golden breeders challenged the circus dog theory as well.

An interesting question arises here. We know that Col. Trench did not like the name of Golden Retriever. Instead, he advocated that the breed be called “Russian Retriever”, which he felt was what the original circus dogs were. Indeed, there are references in the old dog books to a breed of Russian retrieving dogs that, from the written descriptions, were very similar in appearance to the Golden Retriever. In checking, there is absolutely no documentation of any kind that even one specimen of this breed was ever imported to Great Britain. In her book, Mrs. Charlesworth does mention Col. Trench making at least one unsuccessful trip to Russia in an attempt to find and purchase some of these Russian Retrievers to breed into his bloodline of Goldens. So, despite his efforts, it seems that none were ever found or imported by Col. Trench or anyone else.

Why was it that Col. Trench felt so strongly that the breed should be called Russian Retrievers? Is it possible that his ego played a role in this and that he wanted the credit for establishing the breed in England rather than Lord Tweedmouth? Did he resent the credit given to the Lord when he, Col. Trench, had worked so hard to promote the breed and get it recognized by the Kennel Club? Was it that his Goldens were different from those of another well-known breeder of the time, First Viscount Harcourt, whose dogs were called “smaller and darker” than those of Col. Trench? The Harcourt dogs, with the kennel prefix “Culham” also are reportedly traced back to the original Guisachan bloodlines. Why were there such differences in type so early in the history of the breed? We’ll never know the answers to these questions. One thing does seem reasonably certain from all this though: the Golden Retriever is a British breed, not a Russian one.

It seems we know what the breed is not, but what is it? The pictorial evidence that has recently come to light indicates without question that there was some breed of dog that, at the very least, looked like a Golden Retriever long before Lord Tweedmouth began his involvement with Nous. So what was this golden-colored dog in the chromo-lithographs?

An 1802 engraving by J. Scott, shown in the book Royal Sports, has a golden colored Setter shown in its left foreground. In Dogs of the British Isles, the famous “Stonehedge” refers to “Golden-colored Irish Setters”, although he did not consider them to be “good setters”. It is known that the Setters of that time were much more heavily built in body and head than the Setters we know today. Edward Laverack, in The Setter (written around 1915-1920) refers to English Setters of fifty years earlier as follows:

“The distinguishing colour (of the Naworth or Featherstone Setters) is liver and white; they are very powerful in the chest, deep and broad, not narrow or slabby, which some people seem to think is the true formation of the Setter.

If there is any fault to be found with them, it is their size; they are a little too big and heavy.

There is a great profusion of coat, of a light, soft, silky hair … which is rather longer and heavier that the generality of Setters. They are particularly strong and powerful in their forequarters, beautifully feathered on their fore legs, tail and breeches; easily broken, very lofty in carriage, staunch, excellent dogs and good finders. Though liver, or liver and white is not a recognized colour in shows. My belief is that there are as good dogs of this colour as of any other colour.”

Water Spaniel. Original oil by Scottish artist John Carlton, signed by monogram J.C. 1864. Gerald Massey, Britain’s renowned researcher and dealer in sporting art and old dog books, considered the subject of this painting to be one of the three varieties of the Irish Water Spaniel, known as the Tweed Water Spaniel. Though the work is untitled, the dog clearly resembles all descriptive references found to date. Courtesy R. Page Elliott

This description in many ways fits that of a Golden Retriever. It might even be possible that the now undesirable white that sometimes shows up on Goldens today is a “throw-back” to these Setters. Laverack goes on to mention another strain of liver-colored Setters called Edmond Castle Setters. These were “likewise liver and white … These dogs were much lighter and more speedy … They are very deep, wide, and powerful in the forequarters; well bent in the stifles…” It should be pointed out here that during those times “liver” meant any shade of brown, including golden. Could it be that one of these strains of Setters are the precursors of our Goldens? Was, perhaps, Nous the product of some Setter breeding? It certainly seems possible.

Lord Tweedmouth made mention in his studbooks of at least one cross of his “Yellow Retrievers” to a Setter. Perhaps that Setter was one that fit the description given by Laverack. Sampson makes reference to “Cowslip” (out of Nous and Belle) being bred to a Red Setter in 1868. This same dog appears at least twice in the pedigrees of “Prim” and “Rose”, the last two Yellow Retrievers recorded by the first Lord Tweedmouth, whelped in 1889. Was this “red” a golden color? There is then an eleven-year gap from this litter to the earliest recorded pedigrees of Kennel Club registered dogs, that is from 1890 to 1901. What breedings were done during this time? Out-crosses were commonly used to try to improve a breed’s working abilities. Perhaps even more Setter blood was introduced during this time.

In the GRCA archives is a photograph of “Lady”, an early Golden Retriever, sitting next to her owner, the Hon. Archie Marjoribanks, a grandson of the first Lord Tweedmouth. This photo was taken in North America around 1898 while Lady’s owners were visiting here. (A copy of the photo appears in Gertrude Fischer’s The New Complete Golden Retriever). According to Elma Stonex , “99 per cent of current Goldens go back to “Lady”. There is a letter indicating that First Viscount Harcourt (of the Culham kennels of Goldens) obtained his foundation stock of two puppies from a Guisachan keeper who said that the puppies’ mother was “out of a bitch called ‘Lady’ owned by Archie Marjoribanks.” It is considered possible that Lady was out of Prim or Rose, thus making her a descendant of the Red Setter ex Cowslip breeding.

The most famous and influential Culham dog might well be ‘Culham Brass’, a heavily used sire at the time Goldens were first recognized by the Kennel Club in 1901. Assuming that this dog went back to Harcourt’s foundation stock, there can be no question of the influence of the Setter in Golden bloodlines and it is quite possible that one or more of the liver-colored Setters might be included in the Golden’s heritage.

Painted by Edwin Land seer, R.A., London, Published Oct. 28, 1839 by F.G. Moon, Printseller by special appointment to her Majesty for her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent. Steel engraving by Samuel Cousins, A.R.A.

Closeup of Golden-like dog in lower right corner of Landseer engraving. Courtesy R. Page Elliott

.

Highland Gillie. Chromo-lithograph by Vincent Brooks after R. Ansdell, Published Dec. 21, 1853 by Lloyd Brothers and Co. Ludgate Hill. Courtesy of Jennifer Kessner.

What about the Tweed Water Spaniel? The breed is long extinct and there are no identified drawings of any specimens of this breed. However, there are numerous references to dogs coming from the Tweed River area in dog books written during the Nineteenth Century. Hugh Dalziel, in British Dogs, published in 1888, indicates that the Tweed Water Spaniel was a strain of Irish Water Spaniel. Descriptions of these dogs’ temperaments are remarkably similar to one that could be given for any modern Golden Retriever.

The Sportsman’s Cabinet, published in 1803, mentions Water Spaniels, and makes special mention of some of the breed used “beyond the junction of the Tweed with the sea at Berwick”. They were crossed with the “Newfoundland Dog” in an attempt to improve the strength of the breed. This dog would probably have been what is also called the “St. John’s Newfoundland” not today’s breed called “Newfoundland”. An article in the December, 1984 Kennel Gazette (Great Britain) by David Hancock directly relates Golden Retrievers back to the Tweed Water Spaniel and adds that Flat Coats, Chesapeake Bays and Curly Coats are also probably carrying Tweed blood.

So what have we learned? Without question, there was a dog remarkably similar to today’s Golden Retriever in existence well before Lord Tweedmouth began breeding Yellow Retrievers in the 1860’s. That Lord Tweedmouth refined and improved the breed of dog known today as Golden Retrievers is beyond question. But it appears just as clear that others, perhaps even including Lord Tweedmouth himself, had been working with a similar breed of dog, quite possibly a Setter, for some time prior to the 1860’s. Whether these dogs are the “liver-colored” Setters referred to in the old dog books or some other breed is a question that may not be answered with any certainty, but it seems likely based on the available evidence. Since it is known for certain that Lord Tweedmouth crossed his Retrievers with at least one Setter, it seems quite possible that our Goldens owe much more of their heritage to Setters than had been thought previously.

Footnotes:

For further information on the current generally accepted theory of the origins of Golden Retrievers see The New Complete Golden Retriever, by Gertrude Fischer (Howell House), The Golden Retriever by Jeffrey Pepper (T.F.H.); or the Basic Reference Book (Yearbook) published by GRCA.

See accompanying article “The Pictorial Evidence” for full text of printed label on the chromo-lithograph.

Cyclopedia of Painter and Paintings , Champlin & Perkins, Editors. Scribner’s, 1885.

Personal communication from American Kennel Club librarian.

H. Edwin Schaul, The Golden Retriever, Boston, Indian Springs Press, 1954.

W.M. Charlesworth, The Book of the Golden Retriever, London, The Field, 1933.

Edward Laverack, The Setter, page 108.

ibid , page 109.

The Pictorial Evidence

By Jeffrey Pepper

The chromo-lithograph (featured on the cover) that began my quest for more information the origins of Golden Retrievers came into my hands quite by accident. For many years, a friend of mine who breeds Newfoundlands has been collecting artwork and antiques depicting her breed. She routinely visits antique stores looking for “Newfie” items whenever and wherever she can.

About two years ago while on vacation in Rockport, Massachusetts, she went to one of the many local antique stores to see what goodies they might have. While there were no “Newfie” items in the store, there was a dirty old frame containing what appeared to be a color print of two dogs, one of which looked to her like a Golden Retriever. The store owner wanted $60 for the picture, feeling that to be the value of the old hand-made from. My friend called me on the phone and, after describing the print, asked me if I was interested in purchasing it.

I have seen very little artwork with Goldens in it, and most of what I had seen showed poor quality pet type dogs, so I was a bit skeptical. However, even though I’m not much of a gambler, I figured that I could afford the price and asked my friend to make the purchase for me. My friend is more experienced than I in this area and offered the store owner $50, which was quickly accepted.

A week later when my friend returned home I saw the picture for the first time. The frame was in bad shape, its plaster decoration peeling badly and the wood beginning to suffer from dry-rot. The wooden backing material was covered with dirt and dust and the glass was so filthy that it was difficult to see the print beneath it. After some cleaning, it was quickly apparent that one of the dogs pictured was either a Golden or a dog that bore a striking resemblance to one. I put the frame and its contents aside for a time until I could decide what to do with it.

About a month later, another friend who majored in srt history in college and who owns a Golden of our breeding, came to visit. I showed her the frame and picture and she thought it very interesting. The frame, she said, was probably quite old. The imperfections in the glass covering the print were, she said, an indication that the glass was hand-made and of a type that was used in the mid-1800’s. (I thought that the glass was cheap and that’s why it looked funny. What do I know.)

At her suggestion, we decided to remove the wooden backing to check on the condition of the paper the print was on. The wooden slats were held in place by hand-made square-sided nails, another indication of the age of the frame and its print. Once we had carefully removed all of the nails and the wood, a label printed on the back of the print was revealed. It contained the following information:

“THE GAME-KEEPER

chromo-lithograph by Edmund Walker after R. Ansdell Printed by Day & Son, London, England, August 1, 1854”

My friend and I were now quite excited. Chromo-lithographs (“chromo” means, “color”) were common during the mid-1800’s, she explained. Popular artists of the time had their paintings copied in this manner so that the less well-off could afford to enjoy their work. Usually, a lithographer would copy a painting a year or two after it was first painted, placing his (the lithographer’s) name on the lithograph and crediting the original artist. Thus, the lithographer of my new possession was Edmund Walker. The “after” means that the chromo-lithograph is done in the style of a painting done by R. Ansdell. Therefore, the original painting from which this chromo-lithograph was copied probably was done sometime around 1852, or possibly earlier.

I immediately realized the meaning of this. Golden Retrievers were first bred, I remembered, in the late 1860’s. This dog certainly appeared to be a Golden, yet it was dated ten to fifteen years earlier then the time the first Goldens were supposed to be around.

My next step was clear. Some research on the artist was necessary. Again my artistic friend ‘s aid was enlisted. She checked several art history books and found no reference to Edmund Walker. However, an artist’s name. Richard Ansdell, was mentioned! Apparently, Ansdell was a contemporary of Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-18730). Ansdell must have been well thought of since the books indicated that he received large commissions for his original artwork. Further, only the better known artists made it into the history books.

All this made me want to learn more about the painting. I sent photographs of it to a number of people who are recognized authorities on Golden Retrievers for their opinions, including Pagey Elliott, and Joan Gill and Daphne Philpott, two British breed experts. All agreed with me that the golden-colored dog appeared to be a Golden Retriever.